“Why do several things happen to the land when I Just click once?”

Text by Christian Oxenius

Terraforming, the deliberate act to shape a landscape to better fit human needs, has been one of humanities central activities since we started settling in sedentary communities. Let’s just think of dams and irrigation systems, or the extraction of construction materials and minerals from the ground. However, in the past couple of hundred years, the term has taken up a much more sinister turn fuelled by an ideology eager to quantify and thus consume resources actively ignoring the finite and balanced nature of earth’s environment. Nikolas Ventourakis with “Why do several things happen to the land when I just click once?” approaches this topic from today’s perspective focusing especially on the philosophical rationale underpinning the destructive gestures linked to terraforming.

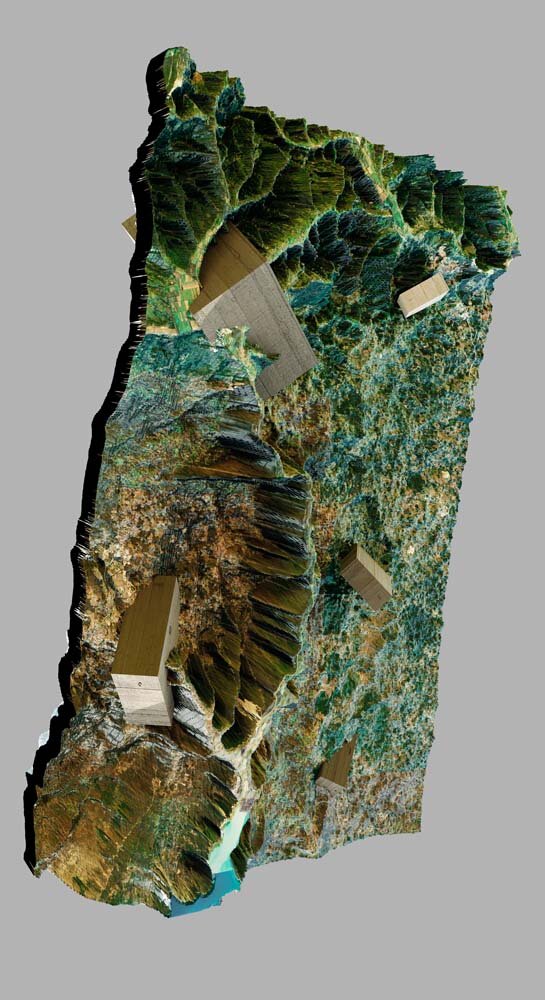

Developed during the 2020 lockdown and a clear rupture from Ventourakis’ previous works in terms of methodology and aesthetic approach, “Why do several things happen to the land when I just click once?” presents us with an image that appears abstract at first. At closer observation the floating mass of earthly tones unfolds into a complex landscape reminiscent of a video game environment or a data-visualisation tool. The viewer would not be mistaken by having this impression, as the work is indeed composed through the aid of a game engine (Blender), through which Ventourakis modifies and reshapes the landscape around Labin, in Croatia. The work, conceived especially for the 3rd Industrial Art Biennial held in Istria in fall 2020 and in collaboration with KORAX (Greece), could be taken as a prototypical example of how artists have adapted and modified their practice in the face of the ongoing pandemic. In a time in which we all find ourselves increasingly limited in our movements and rely more and more on the virtual space for all our needs and desires, the approach chosen by the artist couldn’t be more to the point, especially one whose main tool of expression has so far been led to outcomes hiding experimental approaches inside outcomes resembling photography in its traditional forms.

The conversation with Ventourakis, over the months leading up to the exhibition prior to the pandemic, were focused largely on the key elements found in the landscape in Istria: environmental scars from the past derived from mines and quarries, entire towns developed solely with the purpose of fostering the extraction of minerals, fertile soil reclaimed from the sea and swamps to feed miners, and a myriad of architectural totems, in the form of buildings mostly, erected by each regime who laid claims on those lands.

It is specifically on the relation between the rationale guiding the past authoritarian regimes who ruled (and quite literally shaped) the region and the logic behind so called “Open ended construction building simulations” that Ventourakis focuses in building his reflection and critique. In times in which populism and anti-democratic tendencies are increasingly on the rise worldwide, the works is able to overstep its site-specificity and makes us face deep and uncomfortable questions about the foundation of certain thinking patterns and the actions resulting from these.

The focus on video games seems at first farfetched, however, when we juxtapose the utopic images often heralded by authoritarian regimes as “perfect societies” their rule is promising and the worlds we are asked to construct in games such as SimCity, Minecraft and the like a number of parallels start to manifest. First there is the element of control by a single person (or group) who assumes a god-like status towards an environment or the wider population. This power and its justification towards others are generally based on a self-fulfilling prophecy rationale: the person in charge, by ignoring the complexities of his/her decisions realises projects or achieves goals that appeared too complicated and is thus recognised as a “maker” increasing his/her approval base at the cost of those whose rights are ignored. In video games, and in a way by extension, in a certain type of capitalism born within the same logic, let’s call it silicon-capitalism, the same structure of thinking, elevating specific figures to an almost god-like status, fuelled by para-philosophies such as the one described in Ayn Rand’s writing and other forms of anarcho-liberalism theorists who by opposing the “control of the state” are building the predicaments of a non-democratic/neo-theocratic governmentality.

To conclude and going back to the image Ventourakis presents us, there is an additional element worth pointing out and unfolding more. Within the landscape he created a set of rather harsh and violent interventions in the form of concrete blocks appearing to pierce the generally cohesive surface. The disruptive nature of the gesture is a stalk reminder by the artists of those elements made, as part of our attempt to shape the world in our favour alien to a landscape but “necessary” within the rationale explained above. They act as a reminder of both our tendency, as human kind, to change our environment rather than attempting to adapt to it. What they also appear to point towards is interventions coming from outside the grand plan of certain utopic regimes able to breach the veil of rhetoric ultimately disrupting its fabric.

For an artist whose body of work is largely based on photography, “Why do several things happen to the land when I just click once?” stands out as a welcomed and fascinating research into how to deal with current travelling restrictions but more so, into the way we conceive visual representation of landscapes through distance.

© Nikolas Ventourakis -“Why do several things happen to the land when I Just click once?”,

2020, C-Type on Diasec, 220x120 cm , Unique

Nikolas Ventourakis is a visual artist living and working between Athens and London. His practice situates in the threshold between art and document, in the attempt to interrogate the status of the photographic image. A quest that unfolds in the decisive years of the digital revolution, when a crucial overlap between producers and viewers seems to have reset all previous critical discourses. Central to Ventourakis's visual work is a denial for a one-way resolution and an invitation to embrace an ambiguous imagery, where the photographic is not yet real, and the familiar is a projection of a mix of memory - stemming from both private and media experiences - with abstract thinking. Ventourakis’ fascination lies in our need for stories to be conclusive, which cannot but clash with the impossibility for apparent pictures to provide any evidence nor "objective truth". This is why his work allows for bias and misinterpretation. Whatever the context - a gallery, a page or the screen of a computer - his photographic images seems to have no unanimous foundation and every viewer is left alone to fill in the missing blanks.

Ventourakis completed an MA in Fine Art (Photography) with Merit at Central Saint Martins School of Arts (2013) and is the recipient of the Deutsche Bank Award in Photography (2013). He was selected for Future Map (2013), Catlin Guide (2014) and Fresh Faced Wild Eyed (2014) in the Photographers Gallery as one of the top graduating artists in the UK. In 2015 he was a visiting artist at CalArts with a FULBRIGHT Artist Fellowship and is a fellow in New Museum’s IDEAS CITY. He was shortlisted for the MAC International and the Bar-Tur Award. Recently he has exhibited in FORMAT Festival, Derby; the NRW Forum, Düsseldorf, the Mediterranean Biennale of Young Artists 18, the parallel program of the Istanbul Biennale , Hors Pistes 14 at Centre Pompidou, and The Same River Twice, at the Benaki Museum. Since 2017 he is the artistic director of the Lucy Art Residency in Kavala, and is co-curator of the project “A Hollow Place” in Athens. He is a 2020 Stavros Niarchos Artworks Fellow.

Με την οικονομική υποστήριξη του Υπουργείου Πολιτισμού και Αθλητισμού